The psychology of climate change. Why aren’t we doing more?

My readers know that we should be taking climate change seriously, very seriously. We are educated, articulate, care for the environment, care for each other, and claim to care about future generations. Why are our emissions not falling faster?

Please note that this article is for those based in ‘high income’ countries; ‘low income’ countries have more justification to concentrate on economic growth. I have added links (in brackets) to my previous blogs for those that wish to delve deeper.

I am no expert, but it seems that psychology and social norms trump science. The science is clear. Any warming over 1.5 degrees is ‘dangerous’ (Global Climate Report), yet we are already nudging that level and committed to much more. Impacts will be unpleasant at best, and some will be irreversible. For example, melting ice sheets, sea level rise, and changes in ocean currents (Sea Level Rise).

We lead busy lives, with a range of priorities and pressures. Just getting on with our lives can be enough. Some people have spare money, some get by, some struggle. But more wealth doesn’t seem to be a key factor in taking decisive action. Rich people may invest in solar panels, but overall they create more emissions (The Super Rich).

Parts of the fossil fuel industry must take part of the blame. Like the smoking industry (Smoking and Climate), they have stifled research, misled the public and politicians, and convinced us that there is no alternative. Many politicians, particularly in the USA, receive funding from the fossil fuel industry. Some have run a successful campaign to cast doubt and to delay environmental regulations. Yet, the fossil fuel industry only exists because we continue to buy their products. We now need the experts who work in the fossil fuel industry to invest their talents into renewables and better solutions.

I’m not sure we can place the blame on politicians. Most are good at reading the public mood. Yes, they can be unduly influenced by lobbyists, but they also react to public pressure. They simply don’t receive enough of that pressure.

Public opinion is hard to measure. Whilst polls indicate a majority in favour of more action to tackle the climate crisis, change is never easy in reality. People don’t like being told they have to buy an electric car, or a heat pump, or to eat less meat. Even when the majority is in favour, local campaign groups spring up to prevent or delay action, for example, campaigning against new transmission pylons to transport renewable electricity.

The traditional television and newspaper media have switched their approach in the last few years. Most no longer feel the need to provide a false balance – one story questioning climate change for every story in support of climate change. Of course, there are exceptions, with some newspapers readily taking up any story that criticises the switch to electric vehicles or heat pumps. But overall, the media has ‘got onboard’ in the last few years.

Social media is a can of worms. There is good and bad in it, what else can I say? The unfortunate fact is that it is an ‘echo chamber’ where like-minded people get together, so it stifles polite and meaningful debate. It raises fears or sows the seed of doubt in people who otherwise may act more decisively.

Community groups can, and should be, be part of the solution. But they are often trying to push a boulder uphill. They struggle to make an impact beyond a small group of activists. They can help to enact local change if the conditions are ripe, but we need politicians and businesses to create the right environment for local community action.

Individual lifestyle changes can have an immediate impact (How to Slash your Carbon Footprint). Choosing to share a house will reduce our home emissions, whilst where we choose to live can have a significant impact on our need to travel. However, many of us still perceive it to be desirable to move out of cities into suburbs or the country. Dietary changes (The Mediterranean Diet) are difficult for many and have not been adopted by the majority. Buying less, and producing less waste, sounds easy but we are bombarded with marketing adverts and cheap products (Can we, should we, buy less Stuff?) and have access to poor recycling facilities.

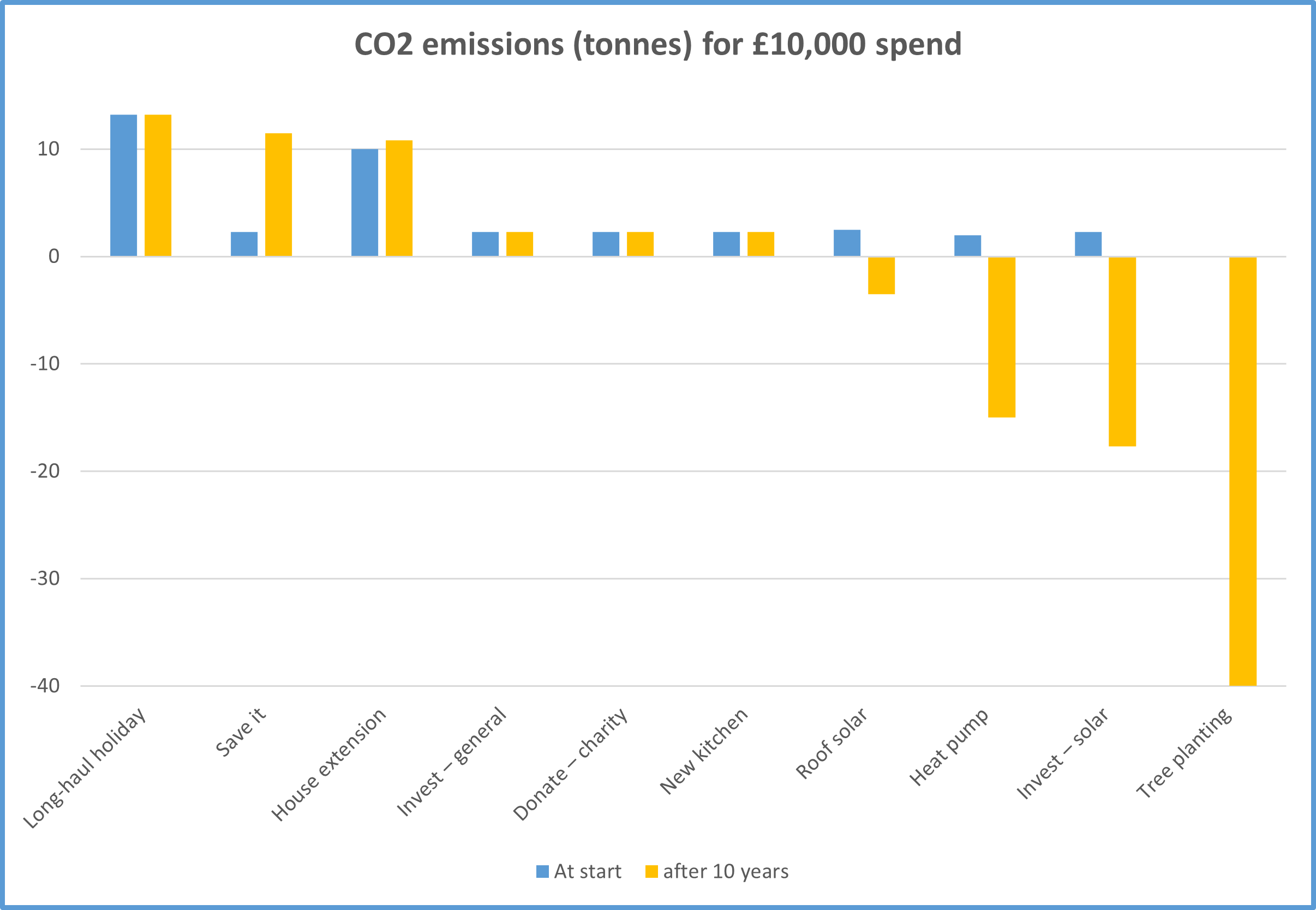

The cost of changing to low carbon solutions is a concern, although sometimes misplaced (Insulate your Home), and based on short termism. Electric cars may cost more but their lifetime costs are now lower than petrol cars. The good news is the dramatic falling cost of solar pv, wind power and batteries are beginning to have a real global impact on carbon emissions (The Electric Tipping Point). However, some solutions are still more expensive, and some will always be so based on current global economics. For example, decarbonising steel and concrete manufacturing is expensive. Meanwhile farmers have doubts about the practicalities of using fewer artificial fertilisers and pesticides.

Economics and capitalism may be an underlying problem. But we are not ready to change tack dramatically. Politicians still espouse economic growth, or, if we are lucky, ‘sustainable economic growth’. There is a concern that if one country stopped economic growth, they would lose competitiveness and strength in a hostile world. However, our economy is based on continued growth which requires ever more energy and raw materials. Efficiency and recycling help but are not enough. And the ‘rebound effect’ is powerful. If, for example, I receive a government grant to invest in energy efficiency at home, this will reduce my energy bills. What will I do with my spare money? I could save it, in which case a bank will invest it in a growing company, or I could spend it. On an overseas holiday perhaps?

Businesses are integral to climate action. In our economy it is businesses that provide the goods and services that we all use. Given the right conditions they can act fast and enable radical changes to happen quickly. For example, new regulations quickly transformed the manufacture of home fridges and freezers to be far more energy efficient. But businesses are still obsessed with growth and this growth often overwhelms the good that they do – they now encourage us to buy larger fridges and freezers (with constant chilled water on tap), then we come under pressure to extend our houses and kitchens to have space for our larger fridges.

Solutions must be practical before we will adopt them. The first electric cars had insufficient range for most people. Today people are still worried about the lack of charging infrastructure. Fortunately, these challenges are being steadily overcome (EV’s: An Honest Assessment). Innovation and government investment can help to lay the foundation for more practical solutions.

With rare exceptions humans act when they perceive an immediate threat. We are not good at long term planning even if it is good for us such as investing in our pensions or looking after our health. Climate change impacts seem like something for the future, although it is already happening faster than predicted. We all claim to care about our grandchildren, but are we acting that way? Short termism is a real problem.

So, you can see that there is no shortage of reasons and excuses for us not acting as fast as we should. But I think there is one more, based on psychology. This is the ‘herd mentality.’ We act based on social norms. No-one else seems to be panicking about climate change. People still buy petrol cars, go on foreign holidays, eat meat. We see adverts for cheap foreign holidays, marketing campaigns to buy ever more stuff which will somehow make us happier. Most people are not out demonstrating and demanding change from politicians. I think we are hoping that it will all somehow be ok, that action will be taken, perhaps the scientists are wrong, perhaps new technology will come to our rescue. It was cold this week where I live, perhaps climate change is exaggerated. Is this wishful thinking? Sorry, but yes is the answer.

Conclusions

Imagine a future conversation with your grandchild. They ask you three questions:

- “Didn’t you know that you were killing the planet?”

- “Why didn’t you stop?”

- “What did you do to tackle the climate crisis?”

Will you be proud of your answers?

In conclusion, I think we need psychologists to work alongside scientists and economists to come up with solutions which are radical, but acceptable to the public (What if?).

Further Reading

ISM (individual, social, material) is a free to use tool to understand and deliver behaviour change. It draws from economics, social psychology, and sociology.

The Climate Psychology Alliance is another useful source.

If you like this blog, please share it.

Carbon Choices

Don’t miss my future blogs! Please email me at This email address is being protected from spambots. You need JavaScript enabled to view it. and I will send you each new blog as I publish them.

You might also enjoy my book, Carbon Choices on the common-sense solutions to our climate and nature crises. Available from Amazon or a signed copy direct from me. I am donating one third of profits to rewilding projects.

Please follow me on social media:

@carbonchoicesuk (X) @carbonchoices (Facebook) @carbonchoices (Instagram) LinkedIn